|

People like their drama and their trauma. They revel in all the excitement.

The histrionics, the temper tantrums, the war metaphors, the plate throwing, the dressing room sulks, the “asshole transplants” *, the scalding of people’s soft bits with cooking implements; this is the way people do their business in high finance, haute cuisine, haute couture, high church, high technology, highly creative arts. It creates a manic economy.

* We learn of a certain executive at Lehman’s, whose goal “to be number one in the industry by 2012, whatever the cost” encouraged aggressive bets in surging asset markets and whose rages were described as an experience analogous to being provided with ‘a new asshole’ and who was ‘affectionately’ known as ‘Darth Vader’.

Subjectively, the financial mania will be over when people get bored of it.

We can’t just blame the politicians and the top executives.

If we induced the companies that provide our everyday products and services to be ISO 9001 certified (just as they impose these standards on their suppliers), then we might deserve more of the following:

-

Ensuring that the objectives of the organization are linked to customer needs

-

Creating and sustaining shared values, fairness and ethical role models at all levels

-

Establishing trust and eliminating fear

-

Establishing clear responsibility and accountability for managing key activities

-

People freely sharing knowledge and experience

-

People openly discussing problems and issues

-

Evaluating risks, consequences and impacts of activities on all interested parties

-

Understanding the interdependencies between the processes of the system

-

Providing people with training in the methods and tools of continual improvement

-

Ensuring that data and information are sufficiently accurate and reliable

-

Making data accessible to those who need it

-

Analysing data and information using valid methods

-

Establishing relationships that balance short-term gains with long-term considerations

Regulation and policing enters the breach where quality management has broken down.

It’s never too late to say that managing the quality in the first place is much the best remedy, as well as being more cost effective.

Severance means breaking a bond. What happens when the bond between success and rewards has been so severely severed?

If the system we use to keep score merely tells us who takes the most, but bears no relation to merit, then where is the motivation to obtain a high score? Past a certain point money doesn’t motivate, but its absence aggravates. In fact, because people look upwards rather than downwards, a high reward can create discontent. The higher you go, the bigger the gap with the next person above.

The best rewards come from real achievement and the sense of self-worth that comes with it.

Seven ideas to make a business work !

1) Turn up (you can only succeed if you’re in the sector)

2) Understand risk (that’s why you’re in the business)

3) Don’t run out of cash (see rule 4)

4) Keep your customers happy (don’t cheat them)

5) Know what things are worth (don’t over pay or under play your assets)

6) Maintain trust (keep communicating)

7) Never give in (keep improving)

We like to put our trust in experts. And we’d rather not deal with those who are not professionals.

And the experts like to be trusted; to get on with their job without being interrupted or hindered.

Similarly, when specialists ourselves we prefer to avoid interference and intrusive control. And if we feel that we do not have the expertise, we choose not to get involved.

Thus, we can get into situations where we trust too much in expertise, though it is impossible for anyone to know everything; and trust too little in those that may not be specialist, but nevertheless may be highly motivated and have much to contribute.

The result is that we end up with products, treatments, remedies, answers that later turn out badly, to our great chagrin and feeling of betrayal. But in reality we have ourselves to blame, and our own lack of diligence, for our regrets.

Likewise we overlook people who know something of vital importance, but who are not recognized as experts. We should speak to the journeyman not just to the star, to the artisan not just to the artist, to the baggage handler not just the logistics expert, the skilled employee not just the managing director, the fisherman not just the fisheries official, the employee not just the managing director, the patient not just the consultant, the commoner as well as the king.

We ignore the customers and the people that really do stuff, because what would they know? We design systems without speaking to users, develop architecture without considering ordinary people.

It’s a pattern of behaviour and, as the saying goes, if we carry on repeating what we’ve always done, we’ll get the results we’ve always had. It’s time to gather information beyond the most obvious sources, and maybe we’ll put an end to a few tragedies and not a few fiascos.

For George Bernard Shaw the biggest obstacle to communication is the belief that it has happened already.

However, a bigger obstacle is the fear that communicating is dangerous. Ironically, this aversion to transparency aggravates risk, because it reduces the supply of information and deprives people of the data that they need to make decisions.

When individuals delude themselves, it’s perceived as madness, when organisations obfuscate it’s understood to be tactful, until all comes crashing down in heaps of confusion, mistrust and missed opportunity.

Communication is proclaimed as a virtue, and yet in the high echelons of our economic and public institutions, concealment and secrecy prevail.

It's wise to ask 'why?'

Patients who ask “why ?” are part of a revolution in health care. As it gathers momentum, we will manage our own health using digital data.

Shareholders who keep asking “why ?” are changing the basis of governance and rewards in board rooms from week to week. They may change the boundaries of the organisation and redefine assumptions about transaction costs and principle agent dilemmas.

Employees who ask “why ?” before applying themselves to a task are forcing senior managers to redefine the way they delegate. This may change the nature of communication in organisations.

A few years ago, in a social experiment, researchers approached the front of a line (queue) and pushed in. When they only said “I have to go first”, it didn’t work out very well.

But, when they explained why, “I have to go first because I have an important job to complete (or a plane to catch)”, then people in the queue (line) were much more accommodating. The interesting thing was that “I have to go first, because I’m in a hurry” worked almost as well.

As a generation of employees (born in about 1980-2000 and labelled ‘Generation Y’, funnily enough) bring their need to be informed to the workplace, they will do more for openness and management accountability than any number of regulatory procedures.

McGregor’s ‘Theory Y’ is based on the idea that work is as natural as play, that people will commit to work and seek responsibility, instead of ‘Theory X’ shunning work and avoiding responsibility. Explaining ‘why’ develops trust as well.

The ‘Five Whys’ (or more if you prefer) is an approach to get to the heart of a problem.

Are ‘whys’ the way to be wise? Interestingly, wisdom has the same Latin root as vision and guidance.

There’s no really good definition of what we mean by “business model”, though it’s certainly a way of organizing inputs to extract value.

However, we recognize one when we see it in practice. Many components of businesses – fast turn-round, low cost, built-to-order, dynamic price, ‘printer and ink’, publisher, leasing, franchise, producer, broker, distributor, customized-service, subscription-fee, web-based, out-sourced, are witness to the utility of a business model.

But, how to build or adopt a business model and fine-tune it? One way is to observe what works elsewhere – in another area of the world – and to work out how it can be imported and made to work locally.

The business model could also be a new and surprising blend of elements that work in another industry; say furniture that you hire, or cars that you build yourself, parking spaces that continually change price according to supply and demand, or meals that are built to order.

Thinking about business models can be a real boost to business creativity.

Many business breakthroughs come from the application of new technologies or scientific discoveries. But, these also deliver a lot of failures due to a misinterpretation of the way the technology can change our basic assumptions.

It was thought that the telephone would be used for listening to opera and that computers would only be used by scientists and the military. The critical factor is often a change in the cost model that enables higher volume and greater accessibility; just as the increased power of microchips constantly release the potential of new electronics functionality.

To recognize a problem or a frustration is perhaps the most successful way to initiate a new business model. We often live for years with imperfections that then turn out to be redundant when finally an improvement is proposed, like music to buy on-line and salads prepared in pre-selected packs.

However good the idea the capital funding never just drops from the skies, generously offered by a beneficent archangel. Even business angels seek proof and reassurance that the big idea will actually work.

Ideas that succeed are often the ones that can be tested quickly in a real-life context. The test should search for flaws. To prove that the concept will really work the customer must make an investment of time or of money. The issue here is opportunity cost. Any idea can seem wonderful until something of value has to be forfeited.

You can’t eat an elephant all at once. You will have heard the expression – it means that you have to slice it up and eat it piece by piece.

Chunking things up, task by task – it’s so easy. You cross the tasks off the list and you know that you are progressing.

Identify the first thing that matters and plan to get it started, to finish it off. Now there’s already a dwindling list. And the mountain doesn’t seem so hard to climb. It’s simple enough. It’s therapeutic. The dopamine kicks in. You feel good.

But, there must be more to life than just a to-do list. Learn to appreciate the moment, the instant, not the past, nor the future, but what gives you inspiration. Create an environment around you that allows your imagination to fly, your spirits to soar and your work to flow.

Don’t give yourself tasks that are too large, too long or too complex. Remember that in a year it won’t all seem so important. Let time take care of itself – other events will happen that will change everything. The future isn’t fixed.

Have a talk with the people around you. Ask them questions. Don’t ever forget to ask why – it will save you so much wasted time.

Avoid unwelcome intrusions. Keep focused on what matters. It’s a project. Manage your own energy and you’ll manage the energy of others.

If you make your list at the end of the day, it will help you sleep. If you do it in the morning, it may be something like this: Switch on coffee machine, heat coffee, put coffee into cups… Life’s worth living again.

I didn’t know how this blog would develop, but now I know that it starts with an elephant and it finishes with an elephant.

Everyone’s list is different. If you touch the leg of an elephant in the dark, you may think it’s a tree, the tail a rope, the trunk a snake, the flank a duck, and if it quacks like a duck. Stop, editor, we have no more time this time.

Imagine a children’s game called the Monkey Tree. Players take monkeys out of the box and hang them on the tree, until the overall weight of the monkeys is too heavy for the tree and then the monkeys start to fall off. Evidently, with the right company and the right number of monkeys, this can be quite entertaining.

To calculate the exact power of a magnet, necessary to know how many monkeys will hang on the tree and how many to put in the box, would be quite difficult. Making a magnet involves immersing the magnet in a magnetic field of an appropriate strength, and making sure that during transportation the magnet is not subject to shocks.

A much easier way is to test the power of the magnet by placing monkeys on the tree. When the monkeys start to drop, then add a few more to the box, package up the game, and ship.

There are many instances in business where the only realistic approach is to try it and see. Business is a feedback game: think about it, plan it, do it and then adjust it on the basis of reactions. However, there could be much more awareness about the importance of testing and experimentation in business.

Unfortunately, the hardest thing about testing is the psychological aspect, because the art of testing is really in the resolve to find as many faults as possible. When a good tester walks into a room, something breaks, and when the testers know why, they feel good about that.

This is not a natural sentiment, it has to be learned. Help a school child to test and you’ll improve their results no end by cutting out some of the stupid mistakes. An entrepreneur sees opportunity. An entrepreneur wants to take out downside risk. They are risk eradicators. A tester ruthlessly hunts down risk. They are fault exterminators.

It sounds similar, but there is a world of difference. An entrepreneur understands the cost model, the communication, the interface, the customer niche, or a combination of these. But the focus on success means that warning signals can get screened out. The tester doubts everything.

Ostensibly there is a similarity between testing and science. But, science starts from a hypothesis. Real science should seek to disprove the hypothesis. But, just as any hypothesis usually has to overcome overwhelming odds before changing conventional understanding, so entrepreneurs have to battle against walls of distrust before winning through.

Science is usually requird to concentrate on one hypothesis at a time (for example, clinical tests deal with one active ingredient and one biological target at a time), where as a business needs to tackle integration and complex interdependent factors.

When there are several factors interacting, the complexity is exponential and potentially beyond reasonable numbers. If you have five factors then each can interact with another a total of 5 x 4 times divided by two, which is ten; but if you have forty-two factors then they can interact 42 x 41 times divided by two, which is more than 861 different two-way interactions, and that’s not counting interactions between several factors at a time.

In the case of the monkey tree, you only have the monkeys and the tree, which is two times one, divided by two is one – pretty simple maths, and very simple for experimentation. However, when there are a number of factors you need to adopt a structured and systematic approach to evaluate enough of the possibilities.

The technique which is known as ‘Design of Experiments’ uses a manageable number of experiments to compare relevant selected factors very methodically. The goal is to assess the impact of the different input variables acting independently, in combinations or in concert.

A legendary example of this was the search for a cure for scurvy – a particularly unpleasant ailment that struck mariners on board sailing ships in the 18th century. By combining different factors such as cider, acid, garlic and fruits the research demonstrated that the best cure was to introduce citrus fruits into the seaman’s diet.

The menu for a ‘Design of Experiments’ approach starts with setting the objective, and defining the variables and finally, having analysed results, selecting the best option. The variables are defined by identifying which are dependent or independent, by defining the possible combinations and by classifying the possible outcomes.

Best practices to take into account are those of randomization (i.e. a non-biased random sample) and replication (the ability to replicate from one sample to the next).

Many trials examine one factor at a time, but the business world is composed of many factors acting together. The design of experiments involving a carefully chosen set of factors has a big contribution to make. Experimentation before implementation makes sense and savings.

Where do the process improvements come from when you have a mature business, heavy infrastructure, huge capital investments and processes that have been worked upon and ‘optimized’ relentlessly?

It sounds trite, but the answer is usually via cross-fertilization, between functions, disciplines, companies and industries.

It always astounds me how often initiatives are kept within the boundaries of one functional area and founder on the borders between disciplines.

The difficulties are due to a lack of mutual understanding. And yet it doesn’t take much to enhance understanding.

Here are some things worth knowing about finance – the notion of payback period, opportunity cost, and the depreciation of assets; manufacturing – the notion of bottlenecks, volume and production scheduling; design – the notion of proportions, layout and cognitive models; selling – asking open questions, handling objections, and closing a sale. And it goes on through the legal domain, human resources, marketing, information technology and so on.

How much time would it actually take to learn about each other’s methods, measures; tools, constraints and key performance indicators? We live and work in a world where specialization is still necessary to cope with the complexity, but where general knowledge is more and more important because of the high degree of inter-connectedness.

An innovation in music involves consumers, producers, musicians, artists, song writers, web providers, advertisers, studios, distributors, concert halls and venues, television and video companies, and consumers’ families.

An innovation in medicine involves patients, friends, families, doctors, nurses, carers, hospitals, pharmacies, medical authorities, regulatory bodies, insurance companies, charitable funds, health organisations, pharmaceutical companies, laboratories, clinical bodies, local health governance, scientists, logistics and communication.

An innovation in aerospace involves tourists, business passengers, airports, airline companies and crews, airline service companies, air traffic controllers, air transport authorities, international security, fire and policing authorities, international equipment suppliers, infrastructure requirments, tax and customs authorities, and local law makers.

All of these different daffy ducks need to line up before an innovation can materialize and enter the mainstream, the mode stream, the bloodstream or the slipstream.

In the field of climate and environmental activities, the world is in a perpetual ‘storming’ phase, which is a project and team building concept that is worth knowing about in all of these other fields.

To leave the ‘warming’ phase and progress in the ‘storming’ phase, you need risk analysis, needs analysis, benefits analysis and to quit the ‘storming’ phase and reach a constructive ‘norming’ phase you requir an agreed work breakdown structure to carry you and everyone forward together.

The challenge for partners in such a dense thicket of interconnectedness is to move through the undergrowth and for that you need a basic understanding of how the other works, and before that the ability to explain lucidly, coherently and with simplicity what one does, why one does it and how one works. How many functions, departments, disciplines, companies, industries and countries are able and really willing to seek to understand and to explain?

Critical Purpose is a new term to define an approach that emphasises the key deliverables. On every project there are a small number of critical questions that must be answered if success is to be achieved. The goal is to isolate these critical success factors and to remove the uncertainties as soon as possible by producing some tangible output that can be dependably validated and indisputably verified.

Critical Path technique identifies the longest path through a project which defines the shortest possible time to complete the project, according to the estimates of how long each activity will take and the interdependencies between activities.

Critical Chain methodology concentrates on rare resource, thus giving it more of a cost focus. By planning around the key constraint and reallocating resources, pressure is reduced on bottlenecks.

Critical Purpose will make people think of agile development methods. However, the word agile can conjure up an image of agitation. The risk is that it over-emphasises reactivity; people may think that if they conceal their intentions, they will be able to make things up as they go along.

Rapid prototyping, risk-based, test-driven, user-centred and team-based are all terms that are used for agile development and each of them emphasises one aspect, whilst in practice the use of one technique makes the others vital.

If you develop the test plans at the beginning of the project, then you are going to need models and prototypes to test many of the assumptions. If you build a plan around prototype reviews, then you will need workshops to facilitate the decision making process. If you focus on risks, then you are going to need the presence of the team and subject matter experts. If you prioritize the requirments then you need to involve users. In fact, of course, you need all of these. It is reassuring to think that if you do one of them, it pulls the others.

‘Critical purpose’ is a term that covers all of these approaches, at least as well as agile because it does not lead people to think that they can decide everything at the last minute, or on their own on their way to work, or without informing anyone of their reasoning.

There is one major skill that does not get mentioned enough on projects and that is about the ability to manage upwards. Managing upwards on projects is not just about the quality of reporting, and it is certainly not a “kiss up, kick-down” mentality, but rather the opposite.

Managing upwards means that the project is driven by a dialogue between the technology and the business. It means that the project manager must validate that the business case is genuinely sufficient to justify the existence of the project, that the requirments have been prioritized with an appropriate break down between what is most important and what is least important, and that the users give reliable feedback when they verify deliverables.

Managing upwards on projects does not imply that designers and engineers, developers and testers, decide what the customer needs, but that they help the customer to frame their requirments in terms that are adequate to start and to continue developing a useful and usable solution.

Managing upwards uses measures and indicators with enough bravery to communicate not only what is important, but also what is easy to measure. It gathers and shares knowledge ('known knowns') as early as possible, admits that there are uncertainties ('unknown unknowns'), analyses and takes ownership for risks ('known unknowns'), and understands that it is the lack of communication across disciplines and up and down organisations ('unknown knowns') that can kill off success.

Managing upwards includs understanding the way different managers and decision makers like to receive their information; some like it in visual format, graphic, text or numbers, or in the right combination, the big picture or the detail, the riskrs, the goals, the actions or the options. It means communicating according to people's preferences.

Managing upwards is about the tactics of delivering the appropriate message that leads to the best decisions; showing red when you need help, orange when problems are under control and green when you are getting the progress and the support that you need. It's about demonstrating that you buy into the strategy and understand the context of the business and not just the project. It's about being a positive team player and not a moaner, and being a leader by showing that you can generate energy rather than stress.

Managing upwards relies on stakeholder management skills, which is another way of saying that you need to understand the organisational and institutional complexities, that you can communicate, lobby, promote, sell; market, persuade, influence and, in other words, exercise political nous in a way that preserves trust.

Managing upwards is a skill that organisations need quite badly as they adapt to a world of changing technological possibilities.

Quality is usually defined as meeting requirments and satisfying the customer; no more, no less.

http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=5150

In this definition ‘too much quality’ is judged to be as bad as too little. There are good reasons for this:

1) Any extra value to the customer should be compensated

2) An excess of unpaid functionality is unnecessary gold-plating

3) Funds would be spent on superfluous requirments

4) There is no way to manage the progress and delivery of excessive functionality

‘Meeting requirments’ means that quality depends uniquely upon specifications and non-specified outcomes are equivalent to defects that reduce quality.

However, my experience is that in practice things are slightly different.

First of all, customers may be unable or unwilling to express their requirments. They cannot express their requirments when they have no experience of the product and don’t yet understand the possibilities.

Unable: If I was asked to specify a whiteboard, I’d be fairly ignorant of the possibilities, especially if asked to look several years ahead. Technology might make it possible to draw pictures like an artist, but should I put this in the requirments? I’d certainly like the feature, but am I asking for something that is too expensive? Compared to people’s likely expectations of what should happen on a whiteboard and the integration of the physical with the virtual, is this likely to be desirable, or mandatory in a few years time?

Unwilling: I may not want to request something for a number of specific reasons. Many people feel that they should buy fair-price, or ecological, or social products, but in practice they buy something else. They may not wish to display disloyalty, or ignorance, or fussiness, or carelessness, or greed, or slothfulness, or for any other reason they may not wish to be thoroughly candid. Thus, many more people claim that they would buy fair-price products, for example, than actually do in practice. Many more people consume fast food than admit to it. People are more likely to vote for re-cycling of materials than actually spend their money on it in practice.

‘Satisfying customers’ implies a price set at where value and price is equal or, as we learned at school, supply equals demand. Hence we converge with micro-economic theory.

Again my experience is different, when it comes to value for money, especially in a service environment.

In a service business it’s easy to think of small details that have a big impact. A smile costs nothing, but it has a big effect on a customer.

The appetizer given by a restaurant that wasn’t on the menu may help the tip. A seat by the window doesn’t cost more to the provider but means more to the customer. That extra glass of champagne in first class doesn’t cost much more, but makes the customer feel special. In second class the same glass of champagne makes the customer feel treated beyond their expectations. Is this bad, if it secures future custom? Luckily there’s a curtain between the two. Meanwhile the cost to the airline is more in the weight than in the cru or the brand.

People don’t say “Oh, yesterday I went to a restaurant that was really satisfying.” If it’s worth talking about, they’re much more likely to say “That was the best meal I’ve had in a long time” (or the worst). And people listening are much more likely to take note and resolve to visit a restaurant that is more than just satisfying. An excellent experience will be retold and may influence several other people, whilst an ordinary experience that’s no more than satisfactory, is more likely to be forgotten.

The fact that someone remembers your name when you go back to the shop, that on the pillow in your hotel you find your favourite chocolate, the hairdresser who knows how you like your hair, the newspaper vendor who knows you prefer not to talk in the morning. A well-run service business is close to a craft. Craftspeople understand that every customer is different. Craftsmanship is not mass production. A true craftsperson puts heart and soul into the details. These small touches that make the object unique and precious, though not always expensive, add more value than they cost.

In my metier as an instructor and facilitator, if I pay 2 euros more for higher quality paper, then that works out at one cent for two and a half sheets, and for that I get the more lustrous feel of the paper, slightly more weight and a noticeable feeling of extra quality, especially for those who are tactile and aesthetic in their appreciation, which is hard to achieve through what I say or do. If I buy coloured post-its and flipchart pens with a nice feel, bold colours and even a pleasant aroma, then at a negligible extra cost, I have an easy win – an enhanced customer experience, and possibly superior to the alternatives.

A craftsman is like an artist. Some, like Van Gogh, paint fabulously, but never get the appreciation during their lifetime. Others, like Picasso, understand how to extract the value in what they do. The story goes that when he found himself short of cash in a restaurant he produced a quick sketch in lieu of payment. The host asked for a signature. Picasso’s reply was that he was paying for the meal, not buying the restaurant. Chutzpah yes, but he knew how to appeal to customers.

Many of us holiday in far corners of the world and have been charmed by beautiful painting, weaving, and carving and sculpture that we have been unable to carry home, due to customs duties or bulkiness. The value exists, but is too costly to extract. Musicians produce music that is as fine as ever and yet current business models don’t enable them to extract so much value. So clearly the perceived value of a product depends upon many other factors, including competitive pressure and the value of alternatives, and these are constantly changing right up to the moment of delivery and payment.

If the price paid by the customer is greater than value perceived by the customer, then value for money is negative and repeat business tends to zero. But if perceived value is greater than price paid, then the sense of positive benefits develops a stock of goodwill that can lead to loyalty from the customer, repeat business, and even new business captured from the competition.

In any case, no organization should invest unless expected benefits exceed expected costs by a calculated amount, and enough to justify spending on this item instead of on something else.

Instead of just aiming at meeting requirments, we should aim to meet the requirments in a way that provides value for money and benefits over time. And the life time value of the experience should at least equal the perception of cost paid. Although value is correlated with cost, it is not the same thing, as we are well able to understand when we consume a beverage or a foodstuff, or use a garment, or indeed any other day to day product.

And when we perceive benefits and cost to be two different curves, then we are more likely to create an environment that accentuates value rather than just interpreting it as being as something that is outside our control, because simply related to cost. In other words, value is the output and cost is the input, two different things.

This is the kind of thing I would prepare if asked to present project management to school students. And I would probably adopt a flipchart style. (This would save having to present a monotonous deck of slides.) I would do something really simple.

First the students would want to hear something about the kind of projects that are done and why they are important all over the world. Students like to hear about the exciting real world and there's nothing more 'real' than a good project! Then I'd explain that projects always bring something new, to the world or to an industry, and they need to be well managed, especially when they are complex and difficult (and they usually are).

Much can go right or wrong, and you can easily rub some people up the wrong way because you are usually replacing one set of things by something else. This means managing the stakeholders' expectations - including customers, but also project participants and team members, other people in the company, investors, the public, etc.

I would explain that projects are always about managing people and their reactions, that is the benefits, as well as the very important triple constraint. I would explain the triple constraint, by saying that delivering quality is about quantifying the expectations of the stakeholders and agreeing on the priorities. I would say that the project has to be organised so that we know what work has to be done to meet expectations and even to give people some nice surprises so that they will want to work with us again in the future.

And I'd say a few words about the work breakdown structure and how you need people to be responsible for all of the different parcels of work that are defined to make sure you meet the objectives. In the triple constraint I would say that sometimes the technical requirments are very well defined, the budget quite fixed and managing the project is mostly about managing time. I would give some examples - e.g. building a metro system or a new airport.

And I would mention the critical path method. I would say that sometimes the date is very fixed and the project content is quite well known, like with the Olympic Games. In these cases, the project is mostly about managing costs and resources: methods such as the critical chain, and performance management (measuring the value of work done) could be mentioned.

I would say that very often in modern business projects the budget is fixed and the time very tight as well, as in launching a new product ahead of the competition. With these projects scope needs to be managed carefully and the project designed so that the most important things are delivered in early versions, according to the critical purpose of the project, which has to be agreed and worked upon with the stakeholders.

I would select one of these projects and talk about it a bit more, making it look and sound and feel very interesting, explaining why it is important, and talking about what can go right and wrong, and why it is a challenge for the companies concerned. I would say a word about how the project manager's job depends upon their ability to operate in a complex organisational context, with the support of a sponsor and listening to the voices of customers and experts.

Then I would say that in general projects are fascinating, interesting, engaging and a good career choice because all over the world, in every industry and in every company and in every department of every company you have new things going on that need good managers.

You don't need to understand all of the technical details, but you have to be able to get people to work together and remember to ask the stupid questions that inspire people to think: like, "What will it have to do to be useful?", "What do I need in order to get started?" and "How will I know when I have succeeded? How can I measure that?" I'd say that it isn't usually very easy to manage a project, because all projects go through a storming phase when people don't agree, and everyone starts to think that everyone else on the project is an idiot. And the students will know this! But, I would explain that the work breakdown structure helps to define all the work leads the project through this stage.

As a conclusion, I would claim that project managers are the people who are needed to turn the problems and challenges of this world into solutions.

Amongst all the processes in a business, project management offers the best possible opportunities for easy wins. However, whilst project management is recognised as being vital to innovation and change management, it is often underinvested due to its perceived difficulty.

These are some of my suggestions for actions that can be implemented in an organisation:

- taking the time to develop a thorough understanding by each of the partners of what the others are doing, both between organisational functions and between clients and suppliers

- performing teambuilding with the tools that will actually be used on the project and then practising using the tools to become familiar with each other’s way of working

- seriously reinforcing the ability to structure the lessons learned from past projects in order to furnish future estimates and anticipation of risks (doing this well is quite rare)

- intensifying the overall understanding of business constraints, benefits and needs, value and costs, opportunities and threats at various organisational levels and across disciplines

- deliberately specifying ambitious constraints that serve as stretch objectives to stimulate creative and integrating solutions and those that necessitate process improvements

- acknowledging that, a project being the essence of disruption, something will change, and even be broken, in the existing procedures and processes in order to achieve success

- taking out the administrative pain from the process and procedures in order to make the process much more attractive and potent through an appropriate and focused minimalism

- beating ‘Students Syndrome’ (doing things at the last minute) by managing the start and finish of activities, and by planning and managing milestones (feet and inch stones)

- overcoming ‘Parkinson’s Law’ by ensuring that trust and transparency allows information about contingency, motivation and competencies to be pooled

- ensuring tighter handovers, fluent transfers and catalyzed interfaces by running the project like a relay race that allows activities to start early if the previous activities are early

- enhancing the culture for visual communication, for using an exploratory scientific approach, graphical instruments, enriched conceptual modelling and tangible prototyping

- integrating methods from program management, problem solving, service and quality management, in order to synchronise best practices instead of a piecemeal approach

- underlining and emphasising core values, such as openness, data focus and no-blame attitude, that allow decision making to be more informed, consistent and sustainable.

It is evident that some of these wins are easier than others, but they are also mutually supporting. Taken as a whole, it would be hard to find other areas in an organisation where investment in methods and learning can have such a large impact (bang for the buck.)

The art is to create a dialogue between market and technology with an evolved attitude of co-responsibility and partnership. This is where to find the opportunities to make significant gains in performance.

What are some elements of a creative and constructive dialogue Y or not X ? '(see below)

Y What it is

X What it isn’t

Y "This is the purpose and the benefit of what we are trying to achieve"

X "I pay; you just get the job done"

Y "These are the outcomes we seek; help us to define the most suitable options"

X "These are my needs; just deliver"

Y "We evaluate the options together and educate each other"

X "I tell you what to do; you execute"

Y "We both think about the price"

X "The value is my secret, the cost is your secret"

Y "We are as transparent as we can be about value and cost"

X "I told you once; don’t ask again"

Y "Understanding is a constant dialogue"

X "I know the answer before we start"

Y "There’s usually more that we don’t know than what we do know"

X "Do it right first time"

Y "Do the right thing and on time"

X "We work with best suppliers; they should do what they are told"

Y "We work with best suppliers; and we endeavour to be a best customer"

X "We have defined our requirments perfectly clearly"

Y "There is no such thing as a perfectly defined requirment; unless we check understanding together"

X "We only progress when everything is ready"

Y "We go forward knowing the risks; and clarifying who is responsible for the risks"

Most creative people are motivated by the potential of what they want to achieve and the competences they wish to acquire. They are looking for transformational business opportunities, rather than transactional relationships. Why treat project teams as if they were disinterested contractors when you can treat them as they are: entrepreneurial stakeholders?

- Providing that you pay them enough, i.e. the market rate, they will be motivated by the potential of achievement, yours and theirs.

- Don’t delegate in a remote uninvolved fashion when you can benefit from real engagement and frequent communication.

- Don’t adopt a superior to subordinate posture, when you can develop a generous, committed and rewarding partnering arrangement.

- Respect the creative process, develop trust not defensiveness, coach each other, and empower them to empower you.

- Share your vision and purpose, explain ‘why’ when you explain something, encourage leadership at every level, stoke the energy and smooth the stress.

There are several web-based business models. Is micro-payments a valid alternative? Micro-payments can allow small payments for valuable intellectual property, which still preserve the generosity of the web, but without dependence on the advertising model.

The question is well addressed in this Stanford project on micro-payments

In my analysis at present, the predominant web-based business models are:

1) All web-site content is free and revenue is derived from data collection (i.e. via advertising based on consumer knowledge) and viral communication.

2) ‘Freemium’, (i.e. free, but pay for added premium value, which could be extra features, enhanced performance, better aesthetics, more user guidance…)

3) A join-up subscriber fee gives access to content, which is sometimes organised in categories according to the value of the subscription.

4) The web site is used as a shop window or as a marketing brochure, which is a supplement to traditional sales and marketing activities.

5) The web site is a service centre to support core activities and develop customer loyalty.

6) The web site as an integral part of the customer and supplier interface (i.e. in essence some effort and costs gets outsourced to customers and/or suppliers).

7) “Brand-me” aims to create a celebrity or brand effect with doses of excitement and ingenuity (it lies somewhere between the blog and the conference model, and often ties to a best seller.)

So the use of micro-payments is possibly an eighth model, and I'm sure there are many others.

Micro-payments compete against free, and like newspapers on the street compared to on-line newspapers, micro-payments can offer content and performance in an agreeable and easily accessible format.

(For example, Apple charges about 1€ or $1 for songs, even though people can download music for free elsewhere, but Apple aims to offer an aesthetic user experience, both on the ipod and on the itunes web site.)

However, the newspaper on-line subscription model has struggled, perhaps because of the aesthetic appeal of paper, the habit and convenience of picking up a paper in a newsagent or due to competition from free news sheets.

For the benefit of small content providers, I hope that micro-payments will grow, but only if it is sufficiently convenient and not all of the ingredients are there yet. It seems to me that it’s still a work in progress.

There is the issue of friction by creating road humps in the flow, surf, crawl and trawl across the Internet. Micro-payments also requirs people to become more accustomed to using a PayPal style account; or alternatively for pioneering credit approaches to develop such as payment via telephone credits, which already flourishes in Africa.

The search is on for the best mix of micro-payments and ‘freemium’ now.

Here is a point of view: It's easier to find things in common between 'Lean' and 'Agile' than differences: both work on the basis of small batch sizes that enable you to get early and frequent feedback; inspect and adapt. Both imply greater 'fitness' (for purpose).

Broadly, 'agile' management helps you to plan and deliver what is necessary and 'lean' management helps you to identify and remove what is unnecessary; so they are quite complementary.

'Agile' includs a lot of 'faiths' and 'values' and I don't even think it's entirely encapsulated by the Agile Manifesto.

Probably, all learning-based innovation should be agile and all agile projects includ some learning.

Meanwhile, you get 'leaner' by removing something unnecessary, like carrying an umbrella when it's not raining, checking your e-mails every 5 minutes, or possibly un-optimised, like travelling to work at the same time as everybody else; although there may always be other risks.

The main risk in 'agile' is that you might not be good at teamwork and team coordination, but that's also the reason for doing it !

So with 'agile' you may have to do quite a lot of experimentation, and 'lean' will help you to make sure that the experiments are worthwhile; quite a synergy then !

Therefore, "Learn to be Lean and Lean towards Agile."

In 'Lean Start-Up' terminology, a “Pivot” is a deliberate adjustment to the basic assumptions about a new product, system, service or process. Implementing the notion of pivots, a company seeks feedback from existing or potential customers and users, early and often, and uses the feedback to change direction, either marginally or fundamentally.

The pivot allows the business, whether it is a start-up or well-established to try things out, to make minimal investments for maximum information. For example, do people want to look at the product on the web and buy in the shop, or look at the product in the shop and buy on the web? These assumptions and what affects them are pretty important. To what extent are people looking for a product, off the shelf and plug and play, or for a service, with advice, support and training?

Who knows? It may only be a small detail in one way or the other that could have significant impact on customer behaviour. Or it could be something more radical, that would enable you to make a breakthrough in technology, marketing and to amend the whole business model. For example, what will users want to do on a phone, a tablet, a PC or in the cloud? The point of a ‘pivot’ is that not only trial and error, but managed learning and revisions, called ‘pivots’ will provide the answers.

Here are some

explanations and examples of different types of pivots, inspired by the Eric Ries book “

The Lean Start-Up” and also by Osterwalder and Prigneur in their "

Business Model Generation" canvas.

(By the way, lean does not mean starved or starving. It means 'fit for purpose', avoiding the useless in favour of useful work, and working on what customers are prepared to pay you for doing, either sooner than later, rather than making up unnecessary things just to look busy. If we were all lean at home, for example, we’d have more time to do the things that we really enjoy and less time on chores and fixing mistakes.)

(Here you can find an instrument that enables you to assess your

leadership preferences).

Importance of project management

Classically, there are two ways to compete in business:

1) By achieving and maintaining low cost and high volume

2) By targeting high value-added and building customer loyalty

The first requirs mastery of production capabilities, whether for a product or a service. The second involves the ability to constantly innovate in order to meet the needs of current or future customers.

However, even production capabilities entail improvement of the process, the methods and the tools, if low cost is not to be based entirely upon low labour costs.

Most companies cannot guarantee the lowest labour costs, and therefore need to compete upon some other basis that demands innovation and not mass production only.

The innovation of products and processes, services and systems, and their development, implementation and development necessitates project leadership skills at all levels, because the effort will be cross-functional and will requir decision making that is strategic, technical, operational and commercial.

Although organisations can squeeze their assets in a production environment over a long period of time, ultimately our economy and our future requir informed and well-instructed teams to innovate frequently and successfully.

Importance of leadership in project management

Companies cannot afford to waste their highly-educated, talented and high potential people resources. Automation, standardisation, routine procedures and high degrees of control are not the right way to release or reward creative brainpower.

Leaders in the organisation must build a climate that encourages inspiration and aspirations, fuels energy and mitigates stress. Creative team members flourish when they have a clear view of the end goal, a sense of purpose and cohesion, an organisation that fits the task, access to information and expertise, working tools, mutual support and recognition for their endeavours.

Leaders need to understand the factors that drive individual and collective motivation. They need to develop values that sustain trust; responsibility, respect, fairness and integrity. They must remain attentive to particular needs as well as managing the dynamics of the team.

Leaders demonstrate courage, tenacity and conviction in order to serve the team and to help them to achieve their ambitions; and they demonstrate the values and behaviours that people want to follow and that preserve their credibility.

Without project leadership competencies at executive level, project management levels and amongst the team members themselves, it is highly unlikely that the innovative products and services that our companies and economy requirs will emerge.

There are more opportunities to obtain return on investment by improving project leadership skills than in almost any other part of an enterprise.

Nature and character of leadership in project management

Project leaders ensure that voices are heard throughout the project and especially in the early stages; voice of the customer, of marketing, merchandising, promotion, production, sourcing, human resources, logistics, finance, safety, regulations, etc.

Project leaders are resolute, honest and forthright when communicating information, from the team to decision makers and from decision makers to the team.

Project leaders seek opportunities to make work simpler, more useful, more usable, more effective and also more interesting, knowing that interested people are more productive in creative work.

Project leaders organize the working environment in a way that respects differences in motivations and priorities that allow people to contribute in different ways.

Project leaders develop a distinctive style that nevertheless takes account of the realities of individual performance, strengths and weaknesses when working in a team.

How to develop a sense of leadership at all levels ?

A project leader may be inclined to a style that is more or less relational, process-driven, ideas-centred or action-oriented.

Relational-centred leadership skills are those that are sensitive and supportive of people

Process-focused leadership skills entail the structuring of change and communication management

Ideas-driven leadership interprets situations and integrates perspectives

Action-oriented leadership shows the way and pursues results with determination

No person can be equally strong in all areas; but the art of leadership is about developing the right balance; the woman or man of the moment.

T

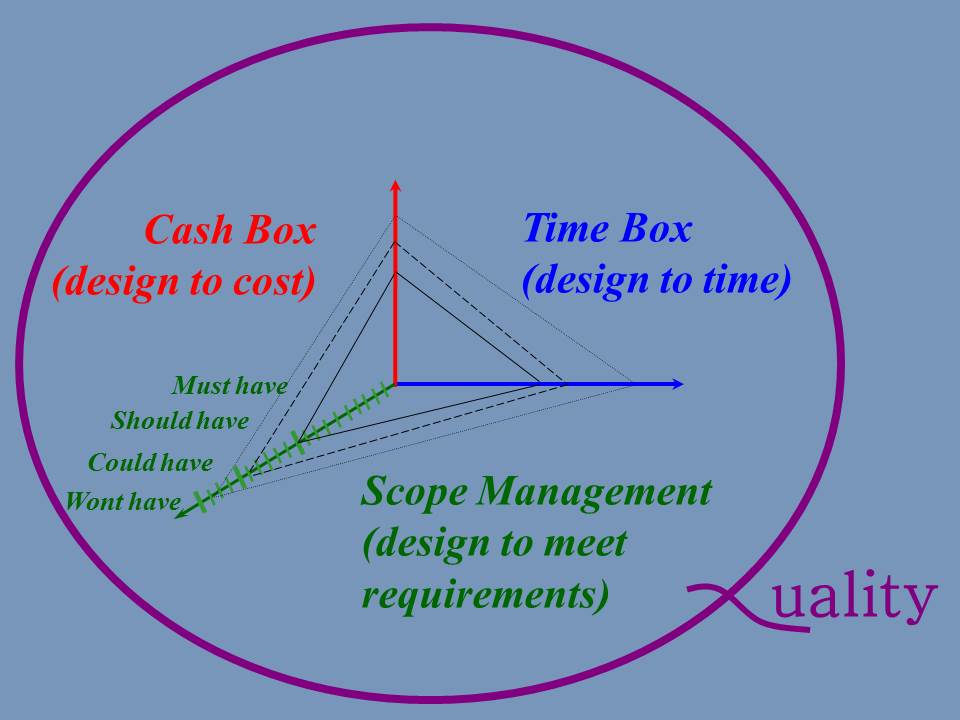

he triple constraint is a cornerstone of project management. However, even if you look hard for it in the PMBoK (Project Management Body of Knowledge) you will not be able to find it. And if you use a search engine, you will find different versions, the favourites being scope – time – cost or quality – time – cost.

Other versions contain resources, risk, performance, and more, making it a hexagon, or perhaps a tetrahedron. Ultimately, the exact form of the so-called ‘triple constraint’ is less important than the fact that there are trade-offs.

This is not a theoretical reflection, but a consideration about what could happen in practice. In fact, it all depends upon the definition of quality. Either the most suitable scope-time-cost combination determines quality, or the quality-time-cost equilibrium defines scope.

If quality is defined in terms of customer satisfaction and meeting or exceeding customer expectations (as per ISO) then quality embraces time and cost, as well as scope. If quality is about compliance with a specification of requirments within budget and on time, then scope covers quality, time and cost.

To satisfy a customer is not to produce a perfect product, but late and over-priced, or to produce the wrong product before the deadline, but cheaply, or the right product on time but at a price no-one can afford. To satisfy a specification of requirments that has been misconceived, or misunderstood, by some of the partners, is not a successful outcome even when it is contractually irreproachable.

An impact on scope, for example, either more or fewer requirments will almost certainly have some kind of impact on the time taken, which will knock on to cost. The inverse is not necessarily true. Prices or exchange rates, for example, can change without any commensurate impact to the schedule, whilst the schedule can slip without modifying scope.

The main reason that leads me to prefer the scope-time-cost triangle is because higher quality does not always imply higher cost. Sometimes, fewer features give a better fit with the customer need, whilst also costing less. Indeed, cheap and quick may be the customer preference, as in many low cost products, rather than waiting for features that provide little added value to the core product.

There are products where cost is embedded as the essence of ‘quality’. It would be entirely inappropriate to suggest an expensive ‘low-cost’ air fare, ‘economy’ car or ‘budget hotel’.

Similarly, there are products for which even the slightest degree of lateness would invalidate any notion of quality: a late ticket for the cup final, today's newspaper delivered 3 days late, a perfect weather forceast (to tell you that it rained yesterday), a gift late for an anniversary.

Here is another version of the triple constraint:

A more extensive reflection on the "

critical triple constraint" and the ways in which projects can be managed according to the priorities established between scope, time and cost also introduces the idea of "critical purpose".

As a LinkedIn survey of July 2013 summarizes: “We get major inspiration hits when we are expressing ourselves, becoming more self-aware and pushing ourselves to achieve new levels of capability. Both requir a ton of self-expression, self-awareness and growth to succeed.”

The LinkedIn survey reveals that we actually become more inspired with age. This is an inspiring thought in itself, because in a sense it means that we all grow

as we age. Amongst the most inspiring professions are those that deal with the arts, education and helping others to realize their potential.

And “If you want to be inspired consistently in your career, you need to find ways to constantly grow and help others do the same. It is that simple and that hard.”

In day to day work, the understanding is that performance = competency * effort. However, this is not the same with activities that involve invention and innovation. Increasing the rate of effort does not necessarily produce more ideas. In fact, it may have the opposite effect by raising the levels of stress and anxiety. Scientific studies have demonstrated how rewards can actually harm the inspiration that drives creative performance. * (See below)

Creative ideas that have the potential to develop into discoveries, inventions and innovations are correlated with other factors, and one of the most important is definitely inspiration. But what is inspiration exactly? First, what is ‘inspiration’ in terms of a dictionary definition?

Putting aside the ‘divine’, and staying in the human domain, definitions includ:

-

the action or power of moving the intellect or emotions (to a high level of feeling or activity)

-

the agent or source of influence or stimulation, such as a flash of inspiration that prompts action

It is recognised that inspiration typically comes from a state of being or experience, that we may be able to anticipate and recognise, such as deep relaxation and meditation, nature or art, human behaviour and uplifting stories, and again the sudden flash of an insight that can arise from a new perspective, piece of information, knowledge or understanding.

Openness to experience precedes inspiration. People when inspired experience more clarity and awareness. And at the same time we may feel more relaxed and confident, as if anything might be possible and the obstacles seem less imposing or constraining.

The feeling of achievement can fuel inspiration as well as being the result of inspiration. Even small accomplishments can trigger inspiration and thus make inspiration a virtuous circle.

From a semantic point of view, there are conditions that are conducive to inspiration, that create a feeling of transcendence, tranquillity, transparency, transmutation and transversal thinking. The “trans” gives the idea of crossing, connecting, blending, and becoming something else through contact with something harmonizing, elevating, and educational or enriching.

From a philosophical viewpoint there is also the sense of synergy and synchronisation, the feeling of oneness and wholeness when things feel complete, fitting, adapted, suitable and appropriate; somehow circular and cyclic, or otherwise expansive and infinite; the sense that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts and beyond the scope of understanding, the feeling that the potential to develop wisdom is perhaps endless.

Furthermore, inspiration can repose upon internal sensations of equilibrium, equanimity, but also can engender excitement, agitation, nervous tension, exuberance and even euphoria. And these feelings can move one way or the other to release inspiration; thus, we are confounded by a contradiction between reassuring continuity, but also the stimulation that comes from change.

Ultimately, therefore is a hormonal reason underlying inspiration. Thus, apparently, inspiration could have a purely physical as well as a purely psychological substance. Psychologically, under hypnosis and with suggestion we can attain a sensation of inspiration. Physically, the hormone dopamine drives the feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment we obtain from achieving an objective. The hormone serotonin contributes to feelings of well-being, inner-contentment and well-being, whilst oxytocin is associated with sentiments of trust and attachment.

Consequentially, and realistically, ‘managing’ inspiration must have implications for the quality of work and for work quality, because it is a basic and intrinsic part of the human experience. We feel better, we work better and we produce better results in creative tasks when we are inspired.

What message can we take away as managers, organizers and leaders?

-

Inspiration can create emotions of exuberance and euphoria, whilst organizations are wary of emotion, preferring logical analysis, cool-headed decisions and rationality in action. Use words such as passion that has positive connotations and make sure that it has meaning, by accepting that passion is made up both of moments of inspiration, and of desperation.

-

Be understanding and supportive about the rhythms, the changes in energy levels; be prepared to mitigate the troughs and to smooth the progress and turbulence over the high peaks.

-

Recognize that different people have different sources and patterns of motivation; in general action-oriented, relation-supporting, ideas-centred or process-driven, but more specifically according to moods, values, lifestyle situation, habits and experience.

-

In further detail, in which situations are people most like to be inspired; start of the day or end of the day, inside or outside, in the city or in the country, amongst people or solo, and for what kind of task or circumstance?

-

Be conscious that inspiration is aspiration, not perspiration; in other words inspiration is “pulled” by dreams and ambitions, by vision and by passion, and not “pushed” by punishment or “forced” by monetary rewards without the feeling of self-realization and attainment.

-

Create an environment that is attractive, aesthetic, stimulating or relaxing depending upon the kind of inspiration which you would like to create. Ensure that meetings and shared work areas enable, rather than discourage inspiration.

-

The best way to find out what inspires people could be to ask them. Then you can help them to realize their aspirations, by appealing to their intrinsic passion and motivations.

As a rule, inspired people have more desire to master work and are less competitive. Inspired people aspire towards higher performance, beyond ordinary achievement, as well as achievements that are more creative an uplifting than routine and mundane. And if people are able to be inspired and to manage their inspiration, with or without outside help, then it promotes their well-being.

* Quite evidently ‘inspiration’ is not the same as what we understand by ‘motivation’; although the

theory of motivation inclines us to believe that many

people misunderstand the application of motivation. Suffice to say, that studies, such as the marshmallow challenge demonstrate the extent to which there are internal ‘motivators’, including inspirations and aspirations, and there are external ‘de-motivators’, which are basically due to the absence of a necessity, such as sustenance and reward or recognition.

The field of motivation is one area where the theory ought to be more respected, because it is much more practical and useful in practice than the various misconceptions and ideologies that people develop about motivation. i.e. If you pour cash down throats, it doesn’t stoke innovation, it chokes it. (It can even encourage the wrong kind of innovation, the one that invents the numbers.)

Try our

motivation exercise to explore the phenomenon of motivation in project teams.

AgilePM is a project management framework for agile projects launched to enable project managers to adopt a mature, scalable, corporate-strength agile approach within their organisations. SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework) is presented as an “interactive knowledge base for implementing agile practices at enterprise level”.

For me, the critical next question for agile projects is about getting top management involvement for projects of high strategic importance; i.e. projects that have significant impact on the future of the organisation. In my experience, strategic decisions in agile projects are being made day-to-day with regard to technologies and customers, whilst unfortunately top managers stand outside the process.

Teams are “empowered”, allegedly (because often without budgetary power), but this does not mean that top managers should be absent. In my opinion, in a highly strategic project they should be available when the situation demands, which may even be in the middle of a ‘timebox’ (i.e. in principle, a ‘sprint‘ does not allow this.)

The philosophy expressed in the '41 things you need to know" is ‘centralized strategy’ with ‘local execution’. But, how does top management participate in ‘local execution’? Think of the way that a Jobs, Gates, Dyson, Bezos or Chanel participates in strategic projects. Give them room and space, but serve, hearten or embolden the team when needed. (Don’t stifle them, but give them oxygen.)

Scrum outlines a ‘Product Owner’ role and I expect SAFe to outline the ‘Product Manager’ role. However, these are often delegated way below the top management level of decision. Given the importance of decisions that will be made during the often turbulent life cycle of an agile project, governance for a ‘strategic’ project must be in the executive suite. How many ‘Product Managers' sit on the board of directors?

I can see the ingredients for top management presence through the ‘Visionary role’ and the guidelines for using the business case in APMG's AgilePM/DSDM,and in the detail of Robert Cooper’s ‘Stage Gates’ (gates with teeth), in design and product development such as Ulrich and Eppinger’s strategic engineering approach via the ‘contract book’, and in ‘design thinking’ in general, and in the IIBA's BABOK. I cannot see it explicitly in Lean for production, but in Eric Ries's Lean Start-Up, via the 'pivots' and 'actionable metrics'. I can also see it as part of stakeholder management in PMI's PMBOK and in APMG's PRINCE2’s exception reporting structure, and in the ‘Sponsor’ role acting as ‘executive champion’, present in all of the afore-mentioned approaches.

For me AgilePM is one way to wrap all of this stuff together and to integrate top management in critical decision making on agile projects of high strategic significance.

If you look at the annual “Agile Tends & Benchmark Report” produced by SwissQ, a consultancy specialising in information technologies and testing practices, on page 4, you can find a maturity curve which shows Scrum approaching post-maturity and DSDM in the introduction phase of the life cycle.

Page 5 reveals that in the survey: “54% of all agile projects fail because of difficulties reconciling the business philosophy with agile values”. “Scrum projects remain islands that are largely self-organized” and only “17.9% use ‘definition of ready’ opposed to 62.1% using ‘definition of done’”.

42.2% of statistics are invented of course. Nevertheless, for me the significance is in the roles. Test consultants recommend an ‘embedded tester’, which is entrenched in DSDM. Scrum insists repeatedly upon the independence of the team from management interference and the role of the Product Owner being to “serve the customer”. (Yep: important to know what the words ‘serve’ and ‘customer’ should mean ;-)

SAFe describes the role of Product Manager in a way which implies top-down management. The Product Manager “communicates the vision” to the team and “maintains the product roadmap”. In essence this role is “typically an active member of the extended Portfolio Management Team, where they participate in decision-making about the key economic drivers for future releases”.

In DSDM, the Business Visionary “defines the business vision”, promotes translation of the vision into working practice, monitors progress in line with the business vision, communicates and promotes the vision to all interested parties, etc. This is potentially a much more pro-active and high-level role.

For me, these are key points: A ‘strategic’ project can give reason to ‘pivot’ the business vision. A strategic agile project may requir frequent re-focusing of the vision during the project. Vision clarification entails active dialogue, trust and understanding between the development team (technology) and the business (market). “Defines the business vision” should allow participation and encourage ownership.

All partners in this crafting and shaping of the business vision must learn to understand the language, not only of the technology (agile and whatever), but of the business.

Do you like stories? In the story about the traveller, the stone-cutter, the stonemason and the cathedral builder, I feel the Scrum teams are like the stonemason, fearful to be turned back into stone-cutters, at a glance from the sponsor or the project manager, where we would have them become cathedral-builders.

A Scrum team may say: “Just tell us what you want, share your priorities and we’ll build it for you; don’t tell us how we should work.” It’s not asking very much and it’s a condemnation of much modern management that expectations are so low.

However, we could offer much more. “This is why we need the work, for which we are accountable; if you can help us with our priorities, you decide how the work will be done.” Providing that the Scrum team show interest in why the work must, should and could be done, it’s up to them how they want to ‘scrum’.

Management stories can be fascinating: At the time of the great cathedrals and other constructions, skilled gang leaders throughout the land; the master masons, architects, carpenters (still ‘maître d’oeuvre’ in French) and the ‘master builders’ like on the great ships (still ‘maîtrise d’ouvrage’ ). The members of the team were later called 'compagnons' in the 'compagnonnage' movement.

These artisans and freemen, staunchly resisting the influence of the church and the aristocracy, created a sense of mystery and ritual. Gradually they edged towards cult-like behaviors, that some trace back to the crusades.

At the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries modern scientific management practices, traceable arguably to Henri Fayol, created the idea of the professional manager. Interestingly, Gantt is often described as a ‘disciple’ of FW Taylor. Given that agile methods can get cast by some as a cult and when innovation teams invest in ‘mindfulness’, we need to keep our feet on the ground and our heads in the real world.

There is a familiar discussion in project management forums about the problems of IT projects, and why information technology projects cannot be more like construction projects.

First of all, I'm not convinced that the Standish Report and other statistics account adequately for projects that are stopped early. If you start a project and stop it the next day, is that a failure or a success? If you stop it after 20% of the work and save 80%, is the project a success or a failure? Was US Airways flight 1549 landed by Sullenberger on the Hudson a failure or a success? When your flight gets cancelled due to weather conditions, do you count it as a failure?

People often tell me that IT projects should be built like bridges. Check how many bridges have the same 'too-thin gusset plates' as in the collapsed I-35W Mississippi River bridge. Did the contractor enjoy the rewards? Henceforth, if future bridges are built more like agile IT projects, there will be more early testing and early prototyping (for example to test the design of the gusset plates) - design of experiments, conjoint analysis, stress loads, ease of assembly, ease of maintenance, risk factors - using physical modelling and computer-aided design - more cooperative and informed decision-making, less nonsense. There will be fewer costly, disastrous and fatal bridge designs. And future failed projects will be corrected, or stopped. Will that be failure or success? Then maybe we will be building cathedrals, not bridges.

If you know the Sir John Egan report, "Rethinking Construction", please convince me that it isn't aligned with agile thinking.

How could we reduce the attrition rate in clinical trials?

“We have thousands of clinical experts and they’ve been working for years on this problem.”

Well perhaps this is symptomatic of the fact that we are looking in the wrong place.

Sometimes the answers are staring us right in the face; sometimes the solution is even too obvious to receive much attention.

There are well-worn and tried and tested ways of doing things, and it’s difficult to question these or even to simply conceive of things differently.

The way that the patient is treated is so important for the way the patient feels, improves, and recovers.

But a patient who fails to fully comprehend what is written in the instruction leaflet, or loses interest, or forgets, or misunderstands is a patient who may be lost to the trial, and also be lost to good health.

Whilst the science of medicine works through consent and ethics, it also includs communication and empathy. In fact, for practitioners of alternative medicines this can often be their only channel, and yet it can have such a potent effect.

Legitimate channels of communication includ the doctor – patient relationship, which can take many forms between considerate and direct, structured and animated. Ethical channels includ press articles and frameworks for advertising and sales.

The leaflet and the labelling are two of the primary channels of communication. The guidelines that exist for packaging are a good example of how to communicate information effectively. Yet many of these guidelines are rarely applied in the spirit of good communication, even if the letter of the regulations is applied.

Regulations underline the importance of making information difficult to misinterpret, difficult to ignore, whilst easy to read, easy to understand, and as intuitive and natural for human comprehension as possible. This is about design: design of the packaging, the labelling and the leaflet that serve to provide the best results.

Amongst the recommendations in the European Commission “Guideline on the Readability of the Labelling and Package Leaflet of Medicinal Products for Human Use” are found information on the type size and font, design and layout if the information, headings, prints colour, syntax, style, use of symbols and pictograms and special considerations for sight impairment. Some of the highlights:

- “Symbols and pictograms are useful providing the meaning is clear and the size of the graphic makes it clearly legible. They should only be used to aid navigation, clarify or highlight certain aspects of the text and should not replace the actual text.”

- “Characters may be printed in one or several colours allowing them to be clearly distinguished from the background. A different type size or colour is one way of making headings or other important information clearly recognizable.”

- “The package leaflet is intended for the patient/user. If the package leaflet is well designed and clearly worded, this maximises the number of people who can use the information, including older children and adolescents, those with poor literary skills and those with some degree of sight loss. Companies are encouraged to seek advice from specialists in information design when devising their house style for the packaging leaflet to ensure that the design facilitates navigation and access to information.”

These guidelines become even more important in an era of electronic communication to a wider and larger sample of the patient population.

It is obvious from reading the text that it is not just a question of the letter of the guidelines, the clauses of the regulations or the chapters of the law. It’s more about the spirit of the regulations than the letters on the page.

Quite simply it is just good design practice to make text, and especially critical medical advice, easy to understand. It is not enough for the leaflet to be understood only by medics with a PHD; it has to be understood by the patient and those who should not be patients.

And this principle can be carried forward into so many other areas of the patient experience that is also governed by regulation. A little more empathic design and a little less bureaucracy good go a long way towards better health care and better return in efforts.

We measure the progress towards a specific delivery defined in a work package and identified by a milestone. The delivery is the goal and the progress measured is the progress towards that goal.

Inevitably there are controls, checks, inspections, tests, validation and verification which guarantee that the right work has been done, to specification, without unacceptable problems, in the right place and in the right quantity: useful, usable and used.

Milestones often release some value that can be recognized and paid for by a customer. The work effort is not always directly related to the value. First of all there is the risk to take into account. Design, preparation and foundations are work packages that may not take a long time, but they can reduce the risks significantly.

Secondly and quite simply, the customer’s perception of value does not always align with the work effort or cost. Information is one example. It may be cheap to give and valuable to receive a piece of information, or vice versa. It’s worth checking frequently what gives the value to the customer – i.e. via prioritizing – in order to adjust the effort proportionately, if realistic and appropriate.

With some work packages a control, a check or a test does not mean very much. Either the work has been 100% completed or not, but there are no intermediate milestones. The work must be accepted at the end, when you can say that it is 100% complete: 0/100